What does Kevin Warsh's nomination mean for the Fed's balance sheet?

Key Takeaways

- Fed Chair nominee Kevin Warsh has proposed shrinking the Fed's balance sheet1.

- The Fed uses its balance sheet primarily to manage liquidity, control short-term interest rates and support the economy and markets during periods of stress.

- The Fed's assets expanded significantly during the Global Financial Crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Bank deregulation could reduce banks' demand for reserves, potentially slowing balance sheet growth, though it's unclear if that would be sufficient to shrink it.

- If the Fed follows a path closer to Warsh's views the yield curve may steepen as lower demand for long-term bonds could drive term premiums higher. Investors may benefit from mixing short and long bonds to balance price and income changes

What are Kevin Warsh's views on the balance sheet?

Warsh has been a vocal critic of the Fed's balance sheet. He contends that multiple rounds of asset purchases1 — known as quantitative easing (QE) — led to an excessively large portfolio. In his view, an oversized Fed balance sheet can distort fixed-income markets and the yield curve by creating excess demand and crowding out private investors.

He also suggests that inflation risks associated with rate cuts (monetary easing) could be mitigated by shrinking the balance sheet 1, referred to as quantitative tightening (QT). Warsh believes with that policy mix, lower rates would support growth, while QT could temper inflationary pressure and market distortions1.

What is the purpose of the Fed's balance sheet?

The Fed manages its balance sheet as a complement to interest-rate policy, with three primary objectives:

- Manage liquidity in the banking system - Bank reserves — deposits held by banks at the Fed — are widely regarded as the safest, most liquid assets in the banking system. Since 2019, the Fed has employed an "ample reserves" regime, which means reserves are maintained at levels high enough that frequent adjustments are not needed to ensure adequate liquidity2. While "ample" is not a precise number, the Fed recently resumed balance sheet growth, reflecting the view among policymakers that reserves are near that threshold.

Maintain control over short-term interest rates - The Fed targets the federal funds rate (the rate at which banks lend to one another overnight) and influences other money-market rates. This is accomplished through setting interest rates on bank reserves and conducting repurchase (repo) and reverse-repo operations. In practice, the Fed:

- Borrows via reverse repos at the bottom of the fed funds target range to provide a floor for money-market rates

- Lends via the Standing Repo Facility (SRF) and the Discount Window at the high end of the fed funds target range to set a ceiling on money-market rates

Reserves, repos and reverse repos are all held on the Fed's balance sheet and adjusted as needed to keep money-market rates within or near the fed funds target range.

- Support the economy and bond market – The Fed conducts QE to add liquidity and support market functioning during periods of stress. This is typically done when short-term rates are near zero and rate cuts aren't an option. QE also allows the Fed to extend the maturity profile of its holdings — boosting prices of intermediate- and long-term bonds, lowering their yields and flattening the yield curve.

How the balance sheet has evolved

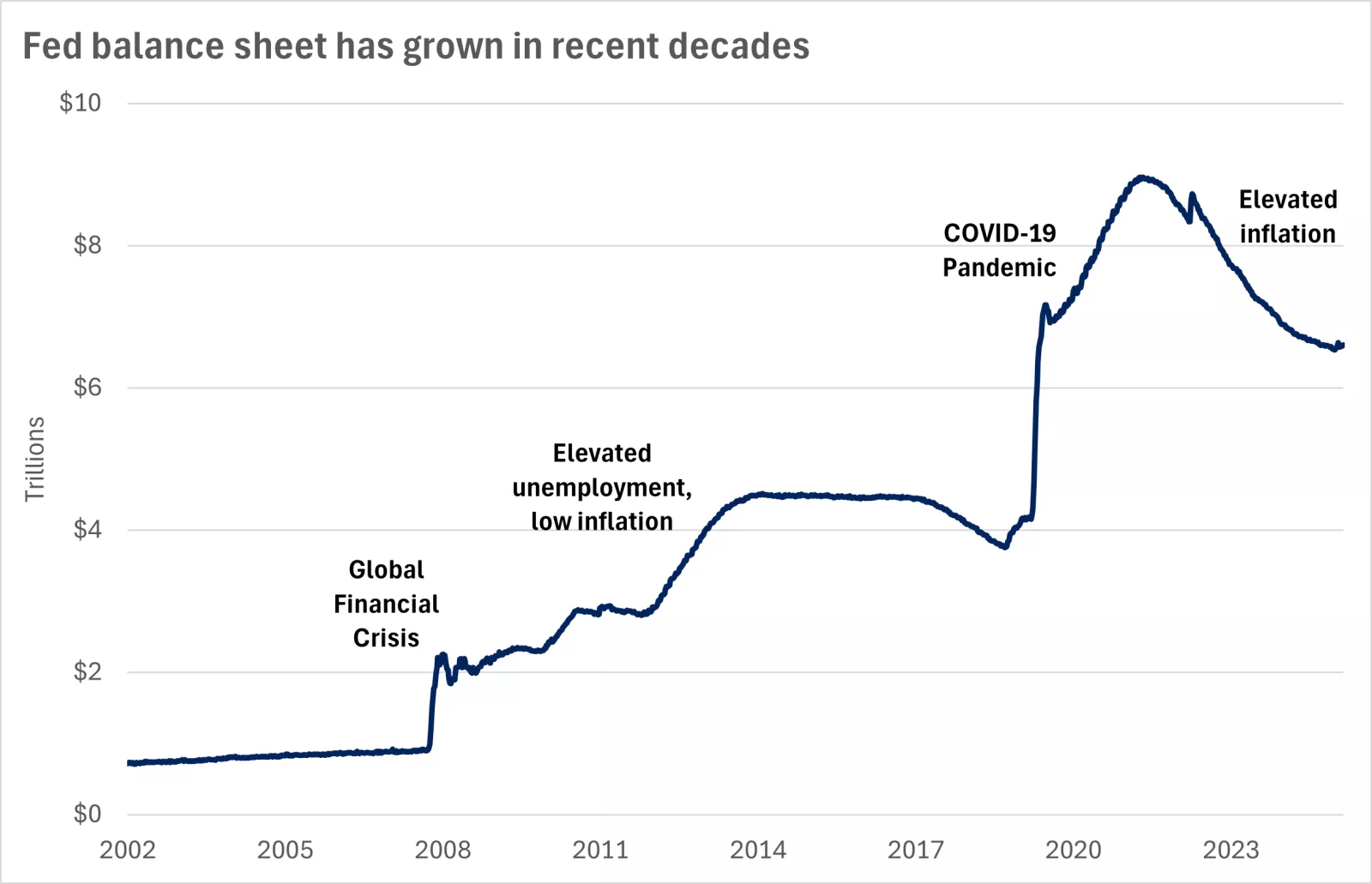

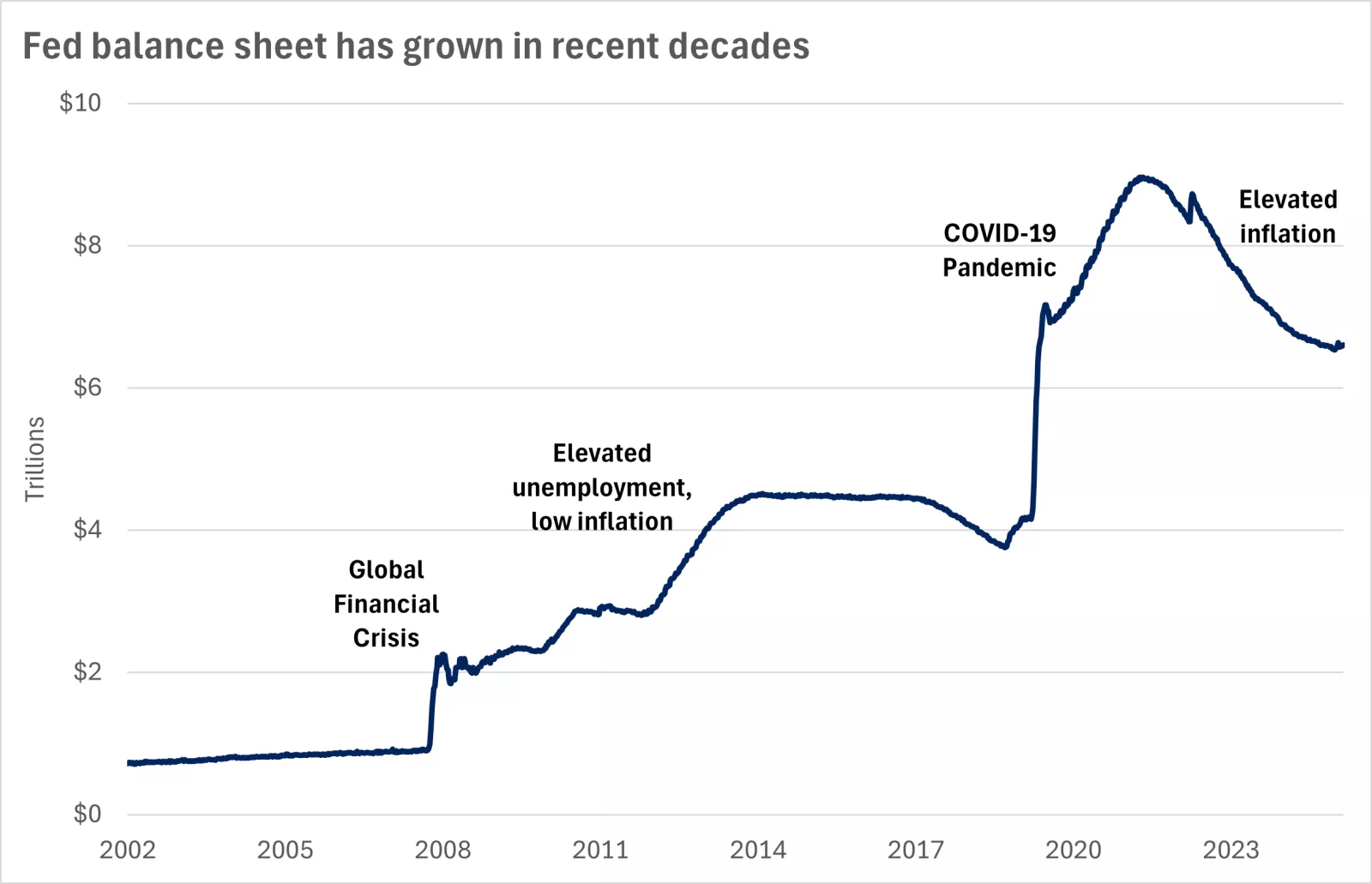

Through successive rounds of QE, the Fed's balance sheet expanded from less than $1 trillion in 2008 to a peak near $9 trillion in 2022. Until December 2025, the Fed allowed its assets to run off through bond maturities to drain excess liquidity and complement rate hikes to fight inflation, shown below:

This chart shows the substantial growth in the Fed's balance sheet over the past two decades.

This chart shows the substantial growth in the Fed's balance sheet over the past two decades.

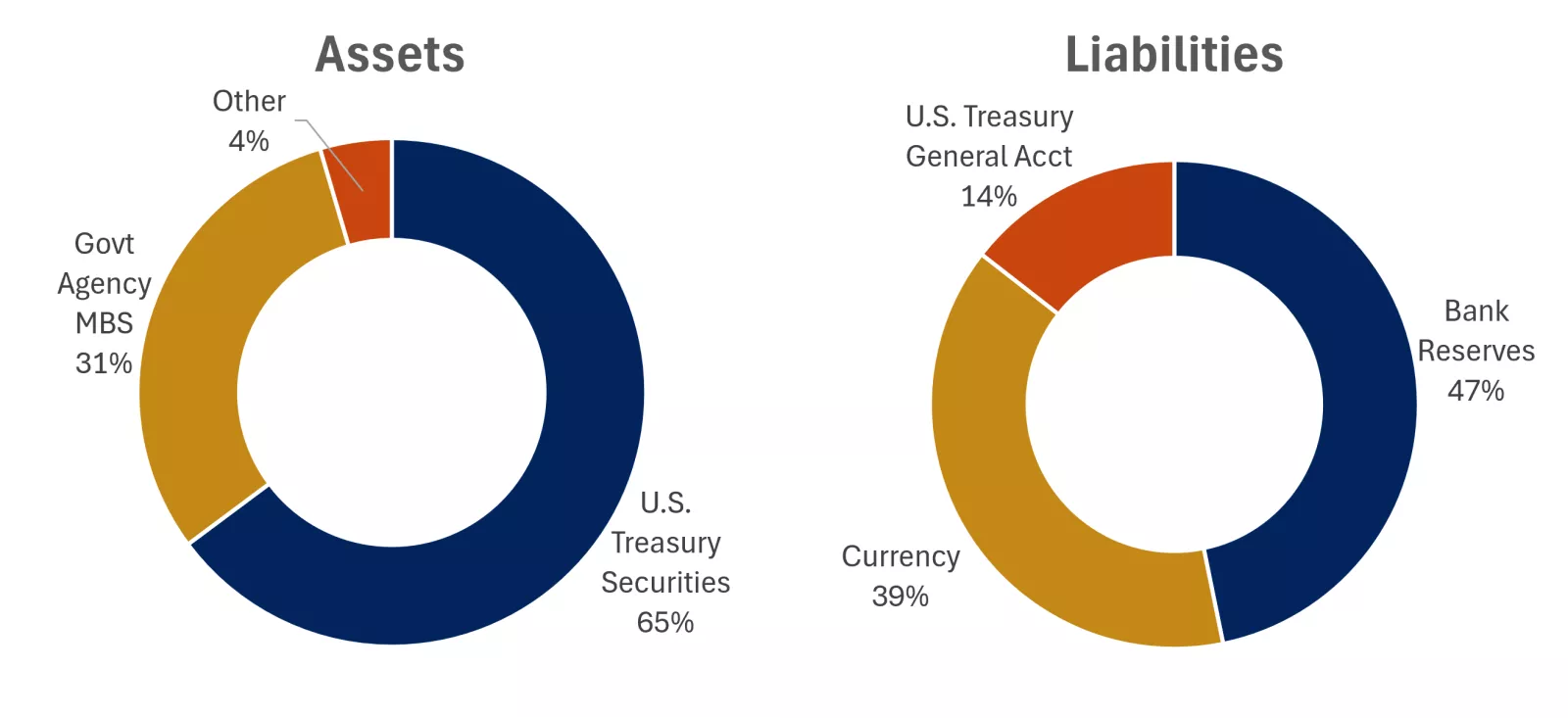

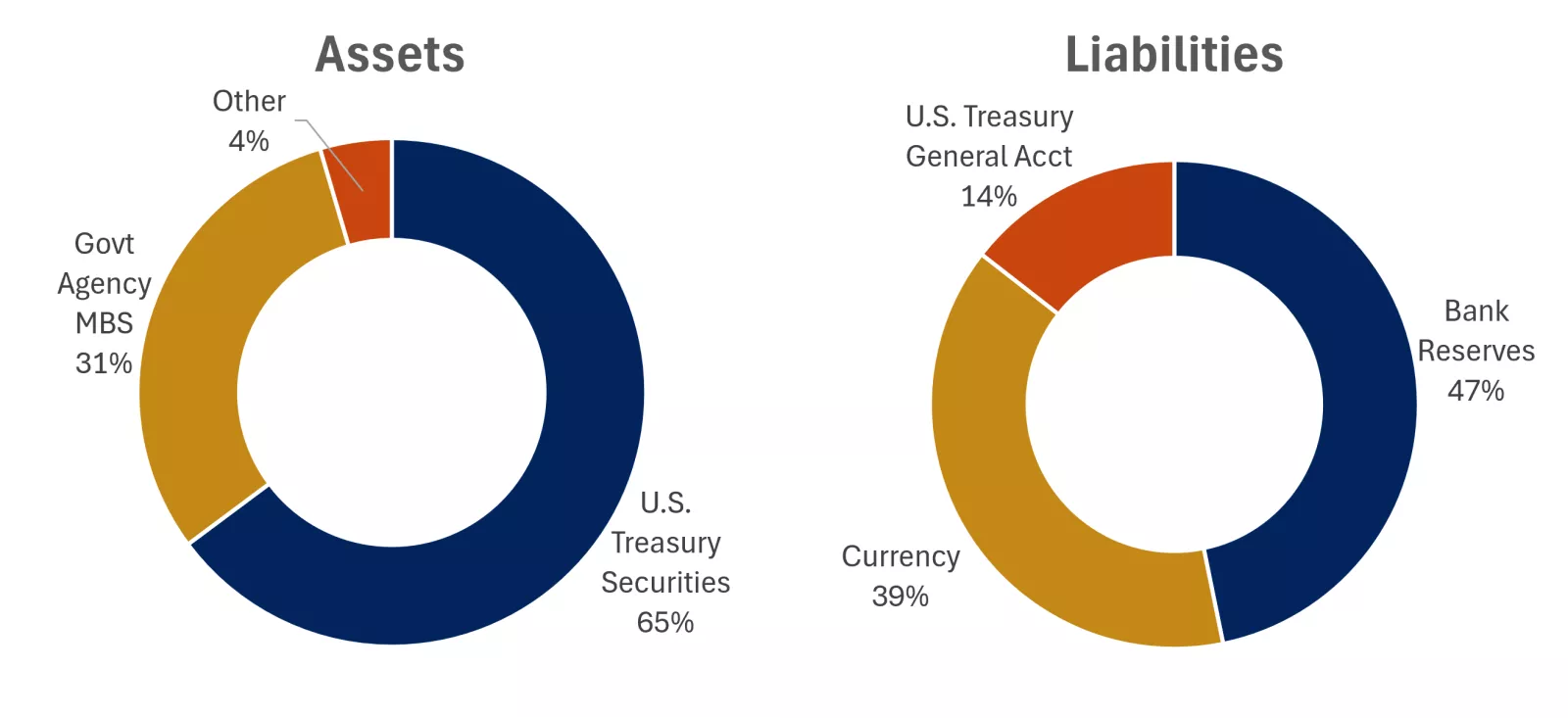

The Fed's liabilities are the key driver to the size of the balance sheet, with the main components being bank reserves, currency in circulation, and the U.S. Treasury General Account (TGA). The Fed has limited direct control over more than half of its balance sheet: currency and the TGA, both of which generally grow along with the economy and the government's budget.

The Fed's liabilities are backed by its assets, primarily U.S. Treasury securities and government agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS) 2, shown in the chart below. Since 2022, policymakers have been transitioning the portfolio toward Treasuries by allowing MBS to decline via principal paydowns. They are also shortening the maturity profile of Treasury holdings to better match the broader market and minimize yield-curve distortions. This is done by reinvesting nearly all principal from maturing bonds into Treasury Bills.

This chart shows the composition of the Fed's balance sheet.

This chart shows the composition of the Fed's balance sheet.

What may lie ahead

The Fed's shift away from agency MBS and toward shorter-maturity Treasuries is likely to continue for years. Shortening the maturity profile of the portfolio means less demand for intermediate- and long-term Treasuries, potentially weighing on their prices and steepening the yield curve over time.

On the liability side, Fed officials have expressed broad support for the ample-reserves framework, implying limited scope for large, persistent cuts in reserve supply. Meanwhile, the U.S. dollar serves as the global reserve currency, which means currency in circulation is likely to grow alongside the global economy, not just the U.S. The TGA generally should trend higher along with the rising federal budget, which involves larger balances moving in and out.

While the Fed appears unlikely to constrain the supply of bank reserves, deregulation could help reduce banks' demand for reserves. For example, banks are required to hold sufficient high-quality, liquid assets (HQLA) to meet regulatory requirements. In addition, certain stress tests require reserves to serve as liquidity rather than Treasury Bills or Discount Window borrowing from the Fed.

As a primary banking regulator, the Fed can relax these rules, though some policymakers oppose such changes. Lower reserves could also free up capacity for banks to lend to consumers and businesses, potentially benefiting the economy. However, even if deregulation lowers reserve demand, that may not fully offset structural growth in the currency and TGA. If it can, the Fed could cut its purchases of Treasury securities, potentially modestly steepening the yield curve.

Overall, to help manage interest rate risk, we continue to recommend holding bonds of various maturities — including intermediate bond funds and ETFs that are typically diversified by maturity. This strategy can balance price and income changes. When interest rates rise, principal from maturing bonds can be reinvested at higher yields or used for spending needs, helping you avoid selling longer-term bonds while their prices may be down. If interest rates drop, longer-term bonds lock in higher yields and likely rise in value.

Sources:

1. The Hoover Institution

2. U.S Federal Reserve

Brian Therien

Brian Therien is a Senior Fixed Income Analyst on the Investment Strategy team. He analyzes fixed-income markets and products, and develops advice and guidance to help clients achieve their long-term financial goals.

Brian earned a bachelor’s degree in finance from the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, graduating with honors. He received his MBA from the University of Chicago Booth School of Business.

Important information:

This content is intended as educational only and should not be interpreted as specific recommendations or investment advice. Investors should make investment decisions based on their unique investment objectives and financial situation. Opinions are as of the date of this report and subject to change.

Past performance of the markets is not a guarantee of future results.

Before investing in bonds, investors should understand the risks involved, including credit risk and market risk. Bond investments are also subject to interest rate risk such that when interest rates rise, the prices of bonds can decease, and the investor can lose principal value if the investment is sold prior to maturity.